IT organizations have the responsibility to rationalize business outcomes with technology driven services to fulfill customer needs. With the prevalence of digitalization and mobile devices, customers are able to consume digital resources more and more using these technology-enabled services. They expect systems to respond in degree of milliseconds and 100% availability. Applications designed with conventional architectural patterns cannot overcome these challenges.

Until recently, enterprise grade applications hosted on tens of servers, respond in seconds and need hours of offline maintenance, and they are subject to gigabytes of data. Whereas due to high utilization rate, data traffic throughout digital channels to servers reached level of petabytes. To meet these demands organizations need systems that are more robust, more resilient, and more flexible. So today’s applications are running on lots of platforms from mobile devices to cloud-based virtual servers that have thousands of multi-core processors. In addition, a paradigm emerged in systems domain began to take more place in technology architecture: Reactive Systems

According to the Oxford Dictionary, there are two main definitions for the term reactive:

Showing a response to a stimulus. - Oxford Dictionary

Acting in response to a situation rather than creating or controlling it. - Oxford Dictionary

As the definitions tell themselves, anything that is reactive needs an external cause or trigger to become active. Based on that context, a reactive system simply keeps up a perpetual interaction with its environment (e.g. human intervention, physical environment, other reactive systems, etc.). As an example, heat energy comprising of a heater and a switch to activate/de-active it is a reactive system that has the ability to react to the user who switches on/off.

The two scientific papers[1][2] that coined the concept of reactivity in system domain also underline that reactive systems have to behave under sequence of events or states, which may also be endless in length.

Reactive systems behave different from computational systems. Programs for computational systems produce some subsequent value upon terminating itself with transforming input into an output, which should be unique. Therefore, non-termination is not an option. Instead, programs for reactive systems perform computation via reacting to impetuses from the environment that they interact. They should work with a non-termination mode. The output they produce do not have to be unique. The input deliberately defines the response of systems in terms of status, actions and outputs as per the nature of reactive systems.

Reactive systems propose a resilient and robust architecture for distributed systems as per their design model. That is why they are increasingly taking place in areas where critical tasks are being performed, massive, unpredictable input occurred, and failure is intolerable such as e-commerce, aviation (e.g. air-traffic management systems, electronic control systems), etc.

Reactive Programming Paradigm

A reactive program is simply the software that drives a reactive system. Reactive programming models carry out loose coupling of application components via enabling them to react to events around them instead of interacting with their ecosystem using formal request/response or command/query methods. This reduces dependencies between components, which paves the way of modularity in the application architecture via enabling to treat input or events as streams to analyze and process.

This paradigm applies to a number of domains that were seen as different in earlier times but have more commonality in fact such as: communication protocols, hardware and software controllers, real‐time process control, systems and HMI (human–machine interface) drivers, and signal processing. Embedded computing which is a special domain of reactive programming has a massive usage in plants, transportation, house appliances, and become pervasive in daily life. The program quality and safety are very important considerations for such mission critical fields of business.

Concurrency and determinism are two crucial tenets of reactive programming. As mentioned before reactive programming establishes an architecture with logically coupled but physically decoupled components where concurrency is must. Most of these systems need to be deterministic where they produce same sequence of output for a given sequence of input. IOW, they need to react in same fashion in same environment, a constraint that is clear in most of the aforementioned applications.

Reactive programming is also a type of declarative programming paradigm that aims to build the program structure with defining logic of a computation without describing its control flow (defines “what” to do) in contrast with imperative programming that defines the computation methodology and algorithm systematically in a definitive way (defines “how” to do). Reactive programming leverages functional programming based on lambda calculus that avoids states, side effects and mutation of data via creating expressions instead of statements and evaluate functions. In functional programming, the implemented function always return the same value for the same argument for the sake of “determinism” in reactive systems.

An example of imperative programming style (JavaScript):

class Number {

constructor(number = 0) {

this.number = number;

}

div(x) {

if(x == 0) {

console.error("Denominator cannot be 0!");

return;

}

this.number = this.number / x;

}

}

const myNumber = new Number(5);

myNumber.div(0);

-> Result: Denominator cannot be 0!

An example of functional programming style (JavaScript):

const div = (a, b) => a / b;

div(5, 0);

-> Result: Infinity

Streams in Reactive Programming

Reactive systems need to deal with asynchronous “stream of events” fired in the environment where they exist. In order to generate tangible and logical insights from these events a reactive application needs to be able to observe these streams, to be able to react on changes around it in a timely fashion and to broadcast relevant data/events based on them. Therefore, reactive programming is a tool for building applications that are asynchronous, non-blocking and event-driven that can easily scale. It also deals with the propagation of change in input.

The term stream merely denotes a sequence of ongoing events “ordered in time”. It can consist of/be emitted in following formats:

- Data (value of some type)

- Error

-

“Completed” signal Several operations are available for stream processing in reactive programming:

- Stream as an input to another one

- Multiple streams as input to another stream

- Merging two streams

- Filtering a stream

- Mapping data values from one stream to another

Marble Diagrams

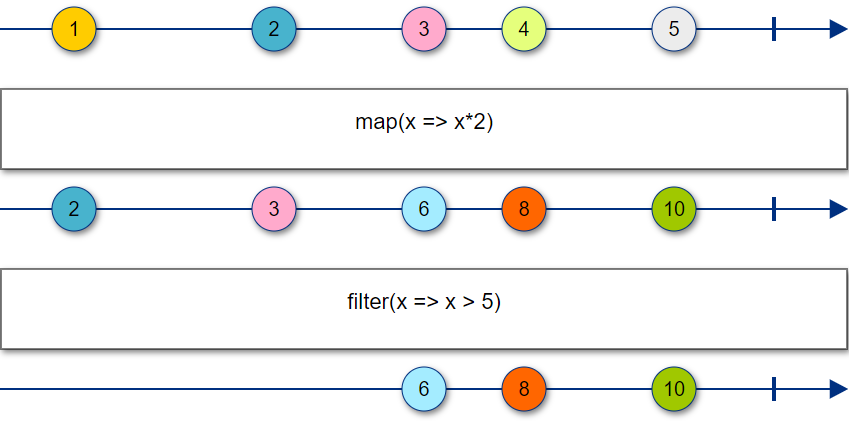

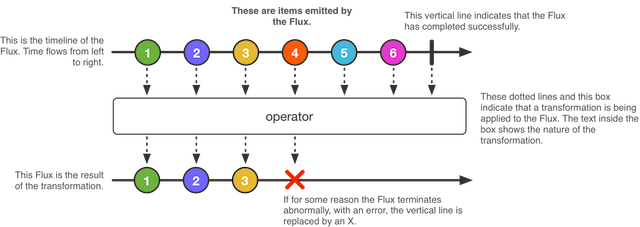

Marble Diagrams facilitate modelling, representation of reactive streams and operations applied on them. Following figure depicts a sample marble diagram for map and filter operations applied to a stream respectively:

The horizontal axis represents time (from left to right). The items on the top axis represent elements emitted and the elements in the bottom axis represent the outcome sequence after invoking the operator defined in rectangle with whatever parameters are specified on the original sequence or multiple sequences in some cases. The vertical line at the end of the axis indicates that a sequence has terminated normally via a completed signal. The ‘X’ on the axis represents that the observable sequence terminated with an error.

Reactor Design Pattern

It can be recalled that one of the important principles of reactive systems is concurrency. To achieve this there exists a design pattern named as reactor design pattern. The reactor design pattern is used to handle requests that are received concurrently by a handler from a single source or multiple input sources. It is the service handler, which de-multiplexes received requests and dispatches them to the related request handlers. In short, this design pattern uses an event loop that runs on a single thread blocking on resource-emitting events and the event loop dispatches the events to corresponding handlers and callbacks.

There is no need to block on input/output (I/O) operations per this approach, as long as handlers and callbacks for events are registered to take care of them. Those handlers/callbacks may consume a thread pool in multi-core environments. The key benefit of using this pattern is that the application components can be divided multiple parts so that it enables coarse-grained concurrency without adding additional complexity of multiple threads to the system. Some popular reactive programming implementations are derived from this pattern (e.g. Vert.x, ReactiveX [RxJava, Rx.Net, RxJS]).

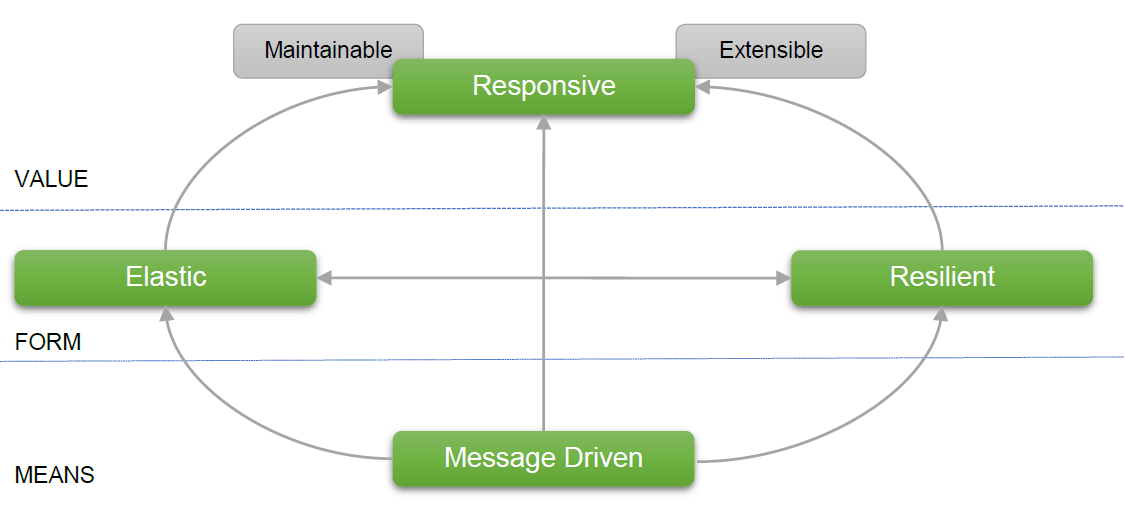

Reactive Manifesto

Reactive Manifesto is an online declaration released in 2013 that aims to shape the foundations of reactive programming paradigm. Martin Odersky (founder of Scala programming language), Greg Young (Coined CQRS pattern), Martin Thompson (High-Performance Computing Specialist) are some prominent figures behind this manifesto. The manifesto preaches four design principles for reactive systems:

- Responsive

- Resilient

- Elastic

- Message Driven

Responsive

According to the manifesto, a reactive system responds in a timely manner. One of the main challenges of the system design is to detect problems promptly and to handle them effectively for the sake of usability and utility. A responsive system has the ability to respond quickly and consistently with setting reliable upper bounds in order to provide a consistent quality of service (QoS). As responsive systems behave in a consistent manner, the error handling becomes straightforward and it enhances end user confidence with fostering interaction with system. This type of system has several measures to achieve responsiveness such as health-check, failover handling, timeout, retry, circuit breaker.

Resilient

According to the manifesto, a reactive system sustains responsiveness in case of any failure. To accomplish this principle the system should support:

- Replication: Ability to execute a service component in different places such as on different threads, processes server nodes, network domains for the sake of scalability.

- Isolation and Containment: Decoupling producer and consumer ends using asynchronous message-driven communication patterns with sustaining their own service logic and life cycle independently and running in different processes. The state, behavior and errors of these components need to be handled and controlled in these components without sharing or cascading to other ones in order to avoid full system collapse in case of failure.

- Delegation: Ability to hand over the processing responsibility of a task to another component such as error handling and reporting functions.

Elastic

According to the manifesto, a reactive system sustains responsiveness in fluctuating load conditions. It has the ability to scale up or down resources allocated to it according to the input volume been exposed to which means to achieve elasticity using predictive scaling methods.

Message Driven

According to the manifesto, a reactive system utilizes asynchronous message driven communication in order to achieve loose coupling, isolation and location independence. The failure is dispatched as messages to error handlers, which are responsible for monitoring errors and if required supervising the components in a centralized and standardized mode. Elasticity, load balancing are fulfilled by monitoring these messages. A reactive system uses backpressure methodology where any component that suffers overhead can give feedback to message senders when to reduce input volume in order to avoid collapsing or dropping messages without control for attainment of resiliency and load distribution. The following image is a basic representation of principles and their internal relations of a reactive system:

Reactive Streams Specification

Reactive Streams specification is a standard defined for asynchronous stream processing with non-blocking backpressure. Its target focus is JVM and JavaScript based runtimes. Due to the nature of Reactive Systems, they need to deal with undetermined volume of data. To overcome with data fluctuation and to avoid system outages, resource consumption of these systems needs to be managed in an elegant way. That is why these systems need to work in asynchronous fashion to utilize computing resources in parallel.

Reactive Streams specification is designed to orchestrate the streaming data exchange through an asynchronous boundary (e.g. moving work on to another thread or thread-pool) while avoiding the process to buffer data in arbitrary amounts at the receiver side. Backpressure is the methodology to bound queues that performs intermediation between threads. To follow the non-blocking and asynchronous behavior of Reactive Streams implementation backpressure signals are also sent in asynchronous manner.

For JVM based implementations of Reactive Streams, following components need to be provided in a way mandated by Reactive Streams Specification for JVM:

Publisher: Provider of a potentially unbounded number of sequenced elements, publishing them according to the demand received from its Subscriber(s).

Subscriber: A generic interface providing 4 methods:

- onComplete(): Notify the subscriber when a publisher is closed

- onError(Throwable): Notify the subscriber when a publisher is closed with an error state

- onNext(T): Notify the subscriber that a message was sent. If everything goes right, after having processed a message, the subscriber will usually invoke then Subscription.request(long).

- onSubscribe(Subscription): Notify the subscriber that a publisher just started a subscription (through the Publisher.subscribe(Subscriber) method). This is also a way for the subscriber to keep a reference on the Subscription object provided.

Subscription: A simple interface acting as a kind of channel description and providing two methods:

- cancel(): Used by a subscriber to cancel its subscription

- request(long): Used by a subscriber to request n messages to a Publisher

Processor: A simple interface extending Publisher and Subscriber interfaces. In other words a Processor can act as both a Publisher and a Subscriber.

Reactive Streams Implementations

There are several Reactive Streams specification implementations. This document mainly focuses on JVM based ones:

RxJava

RxJava is the Java implementation out of Reactive Extensions (ReactiveX) project. ReactiveX aims to concentrate methodologies of Observer and Iterator patterns and functional programming.

Key components that shape ReactiveX are Observable and Observer. An Observable represents any object that can get data from a data source. Its state may be of interest in a way that other objects may register an interest. On the other hand an observer is any object that wishes to be notified when the state of another object changes. An observer subscribes to an Observable sequence. The sequence sends items to the observer one at a time. The observer handles each one before processing the next one. If many events come in asynchronously, they must be stored in a queue or dropped. In ReactiveX, an observer will never be called with an item out of order or called before the callback has returned for the previous item. RxJava has a form of flow control to implement backpressure where intermediate processing steps can express how many items they are ready to process.

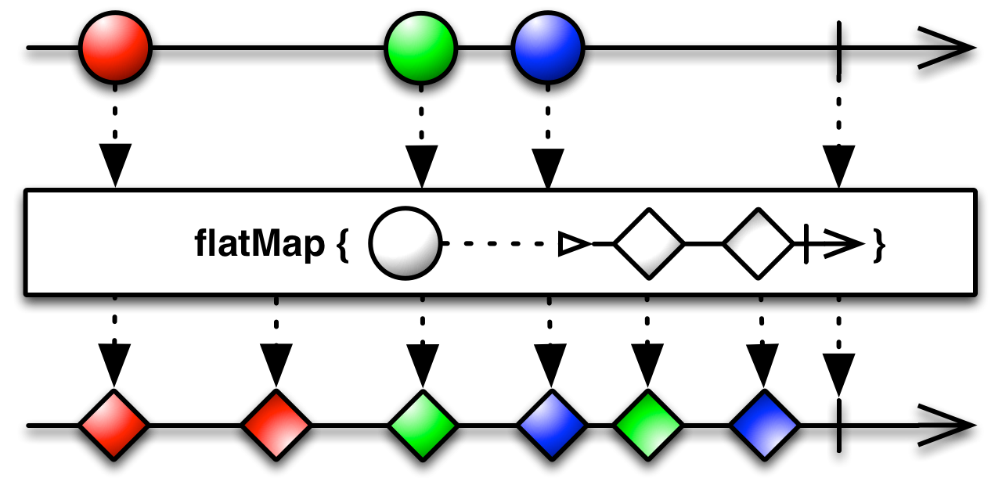

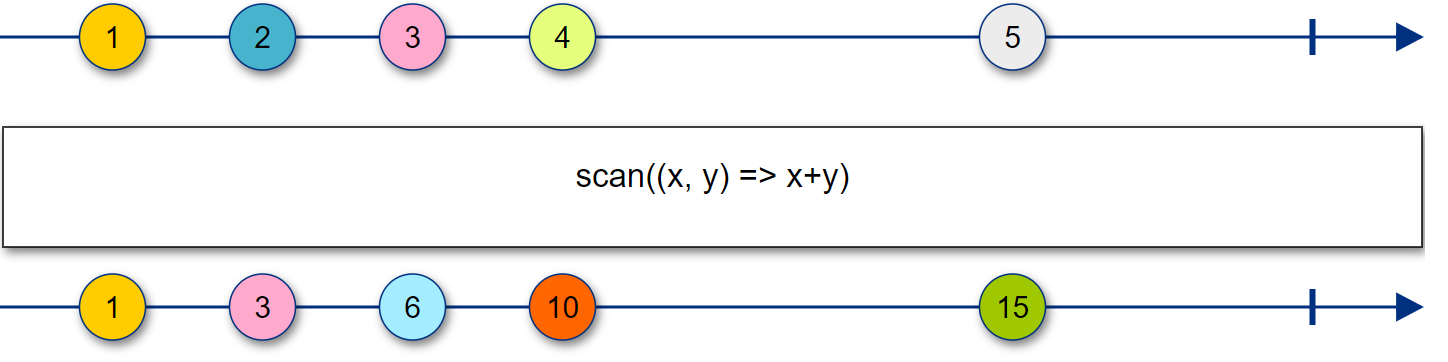

The power of functional programming paradigm is used via operators in ReactiveX. An operator is a function that takes one Observable (the source) as its first argument and returns another Observable (the destination). Then for every item that the source observable emits, it will apply a function to that item, and then emit the result on the destination Observable. Operators can be chained together to create complex data flows that filter event based on certain criteria. Multiple operators can be applied to the same Observable. Some of the well-known operators provided by ReactiveX are:

-

Map: The map operator transforms items emitted by an Observable by applying a function to each item (See Figure 2). Another one related with map operation is flatMap operator that can be used to flatten Observables whenever we end up with nested Observables. As flatMap returns an observable itself, it is perfectly suited to map over asynchronous operations. Here is a marble diagram of flatMap operator:

-

Scan: The scan operator applies a function to each item emitted by an Observable sequentially and emits each successive value. Here is a marble diagram of scan operator:

-

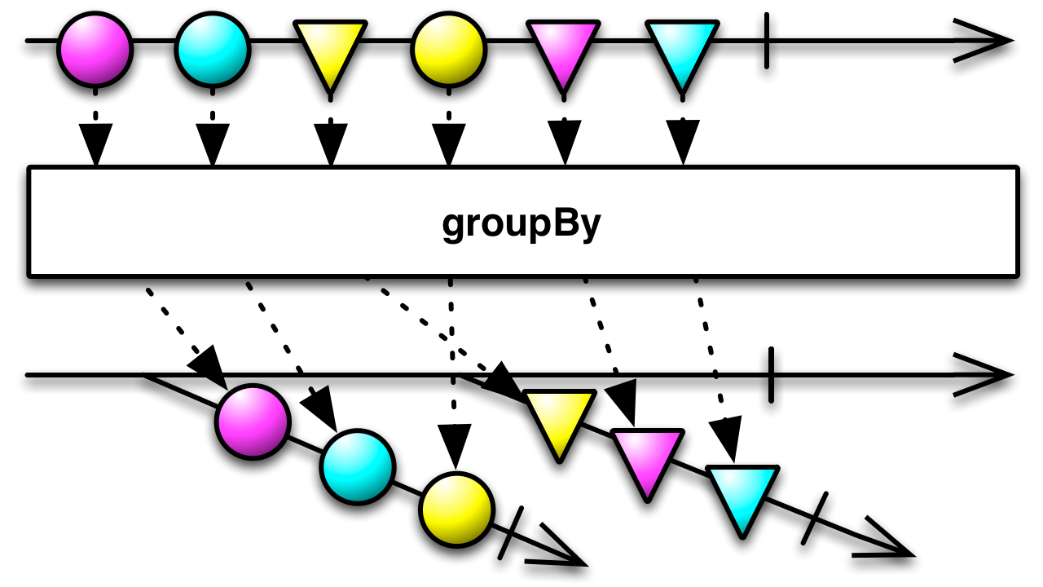

GroupBy: The groupBy operator allows classifying the events in the input Observable into output categories. Here is a marble diagram of groupBy operator:

-

Filter: The operator filter emits only those items from an observable that pass the test defined via a designated predicate (See first marble diagram. Predicate there is x>5).

Project Reactor

Project Reactor is Reactive Streams compliant JVM based implementation provided within Spring Framework (as of version 5.0) by Pivotal. It is based on Reactor Core and IO modules that expose Reactive Streams constructs, which provides the ability to use Spring, RxJava, Akka Streams, etc. On a modest hardware configuration, Project Reactor based applications can handle high data throughput. There is also out-of-box support of backpressure ready network engines for protocols HTTP (including WebSockets), TCP, UDP with reactive encoding/decoding ability. To implement Reactive Extensions Project Reactor provides two types of APIs:

Flux [N]:

- A Publisher with basic flow operations

-

Emits 0 to N items asynchronously

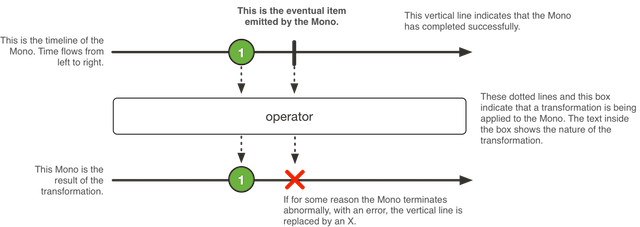

Mono [0|1]:

- A Publisher constrained to emit 0 or 1 element asynchronously

-

Deterministic 0 or 1 sequence generation

Projector Reactor based applications have ability to work with three working models:

- Deferred: No input emitted by source until needed by downstream.

- Pull: When consumer is ready to consume input it signals to the source. The client literally pulls the data down to the stream.

- Push: On retrieving a go signal from consumer, the source pushes data down to the stream until it gets stop signal from consumer.

The backpressure implementation in Project Reactor uses a bounded RingBuffer data structure to mitigate signal-processing difference between producers and consumers via storing, exchanging and parallel coordinating of pushed signals. It is based on a library named as LMAX Disruptor that proposes a high performance inter-thread messaging library. Operators, processors and any standard components working on the sequence are instructed to pour the data when these buffers have room.

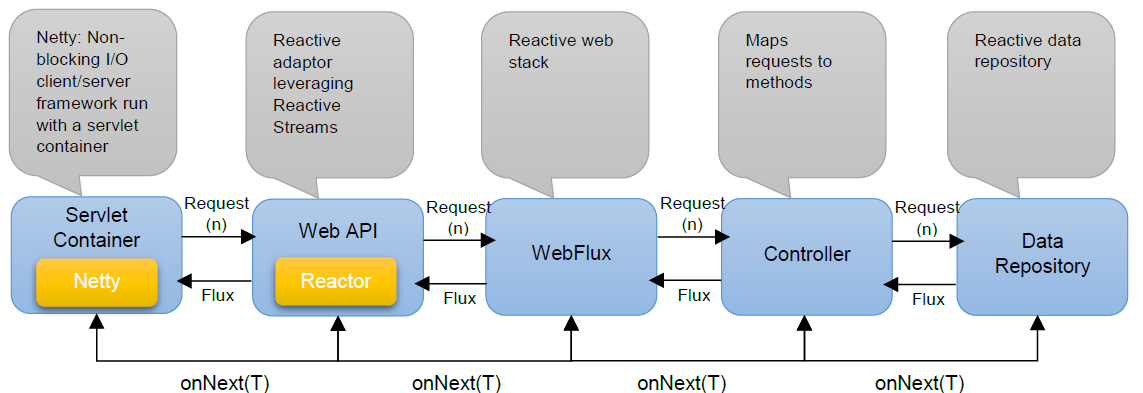

Spring WebFlux

Spring WebFlux offers capabilities to implement reactive HTTP and WebSocket clients as well as for reactive server web applications. It leverages Project Reactor under the hood and part of Spring 5. WebFlux can run on Servlet containers that supports Servlet 3.1 Non-Blocking IO API as well as on other asynchronous runtimes such as Netty and Undertow. RESTful JSON and XML serialization and deserialization is supported on top as a Flux

Akka

Akka is a combination of open-source libraries to implement Reactive Streams specification for Java and Scala programming languages with providing the capability to span the application through processor cores and networks. Akka makes use of the actor model to provide a level of abstraction to facilitate implementing concurrent, parallel and distributed systems.

An actor is simply a container of following items:

- State: Variables to reflect possible states of actor

- Behavior: Actions defined when reacting to message

- Mailbox: Used to enqueue senders’ messages in time-ordered fashion

- Child Actors: Actors that has sub-tasks delegated on themselves by their parents

- Supervisor Strategy: Supervision describes a dependency relationship between actors. The supervisor delegates tasks to subordinate actors and therefore must respond to their failures. To perform this a supervisor designates action set to handle faults, messages, execution environment (thread pool management) and address (location to send messages).

In Akka everything is an actor and is also a computational entity. Actors respond to message with concurrent fashion. An actor can also have the ability reacting to a message by sending messages to other existing actors in application or by creating new actors. Therefore, actors have the liberty to designate how it will respond to the next incoming message.

The main feature of actor model is to provide an abstraction of communication for the sender. Recipients of messages are identified by their addresses. Moreover, actors can only communicate actors with same address. Actors can obtain address form a message and retain the address of actors they created. The actor model provides a means of achieving concurrency among actors and the dynamic creation of actors. Interaction between actors only occurs through asynchronous message passing with no restriction on message arrival order.

To support event-driven principle of reactive systems, actors perform work in response to messages and the communication between actors is asynchronous. As actors does not have a public API, isolation principle is fulfilled and the actors can be utilized via messages that they need to handle. Actors are constructed from a factory. They can start, stop, move and restart to scale up/down as well as recover from unexpected failures to support elasticity and delegation principles. Each actor have only a few hundred bytes memory footprint.

To reap the benefits of actor model in Akka following best practices should be followed:

- Use descriptive names for defining messages.

- Messages need to be immutable.

- Put an actor’s associated message in static classes as inner class within the Actor class to be able to make messages immutable.

- Use static

props()method in the actor to describe how to construct it.

The actor system, that is the logical organization of actors in hierarchical manner, takes a complex problem and recursively splits it into smaller sub-problems. Akka ensures that each instance of actor runs in its own thread and that messages are processed one at a time.

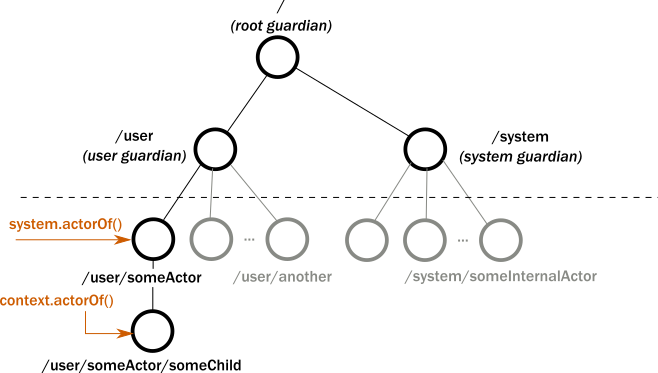

Akka generates three base-actors on startup:

- Root Guardian: The parent of all actors in application

- User Guardian: The parent actor for all user created actors

- System Guardian: Supervises an orderly shutdown sequence

Actors supervise their child actor in their own path. Here is a figure on Akka actor hierarchy[10]:

Vert.x

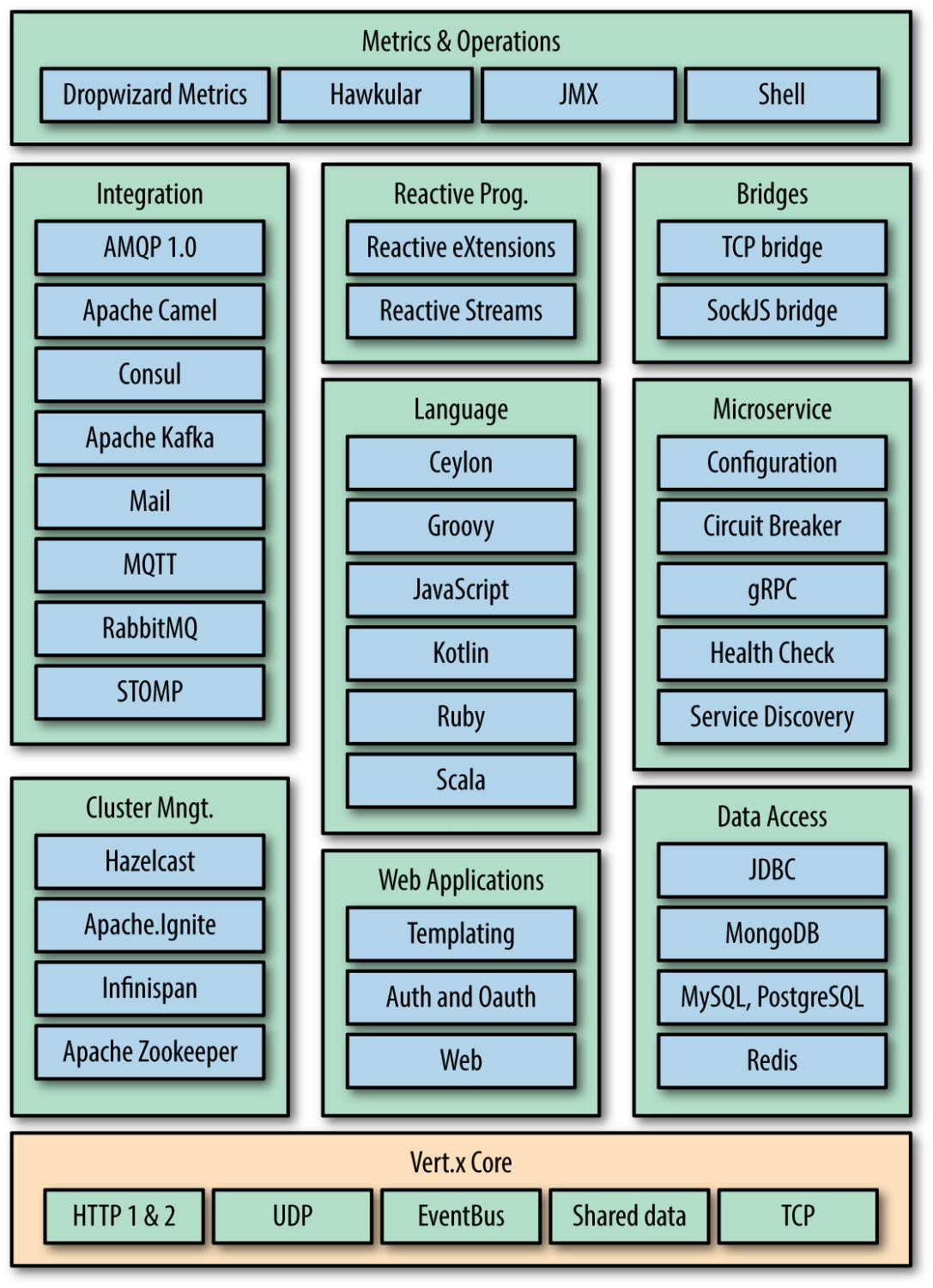

Vert.x introduces itself as a toolkit for implementing reactive and distributed applications based on a development model that is asynchronous, event-driven and non-blocking. It is possible to implement Vert.x applications using different programming languages (Java, Scala, Ruby, etc.) and blend Vert.x with other frameworks (e.g. SpringBoot). It has a modular architecture with different set of JARs under the hood. One can add a Vert.x module JAR(s) as a dependency on top of Vert.x core JAR to enable the relevant functionality.

A Vert.x application has the ability to react events around it using handlers. These handlers do not block the execution and are called when an observed event fired or an asynchronous task is performed. Usually, a single thread named as “event loop” performs the invocation of handlers. As a frontier, the event loop interacts with a queue of events and dispatches them to relevant handler(s). Due to this method, there is no challenge to maintain concurrency as this single thread is responsible to perform mediation between events and handlers. If nothing blocks the event loop (exceptions are database accesses and heavyweight computations), which is essential, the application can process massive event loads in a short time frame that fits reactor design pattern. Vert.x has also the ability to manage different event loops with affining them to different CPU cores.

Vert.x proposes the ability to develop self-managed applications based on an actor-like deployment model using building blocks named as “verticle”. Verticles are deployable and runnable code snippets (implementation of Vert.x verticle interfaces) that can be written using programming languages supported by Vert.x. Any Vert.x application can host different verticles written with different programming languages. These scalable pieces shape the overall Vert.x application and communicate with each other via messages. Handlers, server or client implementations, business logic of a specific task is embedded within the verticle. Some of Vert.x capability domains and modules can be depicted as follows[12]:

Conclusion

Reactive Systems encounter with indeterminate input. The input to the system keeps changing per events that are originated by the environment, and so does the response of the system to this input. Hence, the main objective of reactive systems is to provide a run-time processing assurance of the input based on its constraints (e.g. data rates) at run-time, apart from the actual input that may be applied at any time to the system.

Systems built as Reactive Systems are more flexible, loosely coupled and scalable. This makes them easier to develop and amenable to change. They are significantly more tolerant of failure and when failure does occur, they meet it with elegance rather than disaster. Reactive Systems are highly responsive, giving users effective interactive feedback. The largest systems in the world rely upon architectures based on these principles and serve the needs of billions (There is a real life example how Netflix services were not affected by a complete AWS availability zone outage because of adhering to these design principles.).

There also exists a sample project in GitHub, which displays real-time Bitcoin price via a very simple web interface. The project was implemented using aforementioned reactive programming implementations.

References

- D. Harel and A. Pnueli, “On the development of reactive systems” in Logics and Models of concurrent Systems, NATO ASI Series, vol. 13, K. R. Apt, Ed. New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. 477-498, 1985.

- Pnueli, “Applications of temporal logic to the specification and verification of reactive systems: A survey of current trends”, in Current Trends in Concurrency, de Bakker et al., Eds., Lecture Notes in Comput. Sci., vol. 224, Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag, pp. 510- 584, 1986.

- A. Benveniste, G. Berry, “The Synchronous Approach to Reactive and Real-Time Systems”, 2002

- K. Pratap, Shelja, M. K. Bedi, “Formal Specification and Verification of Reactive Systems” in International Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & Management, 2013

- G. Berry, “Reactive Programming” in Encyclopedia of Software Engineering, 2002

- J. Bonér, D. Farley, R. Kuhn, M. Thompson, “Reactive Manifesto”, 2013 (first release)

- Reactive Streams

- ReactiveX Documentation

- Project Reactor Reference Guide

- Akka Documentation

- Vert.x Documentation

- C. Escoffier, “Building Reactive Microservices in Java”, O’Reilly, 2017

- Spring WebFlux Documentation